People who are gifted may be hard to identify. For example, curious children who feel bored in school, adults who have difficulty making career decisions or relating to other people, and homemakers who suppress their abilities in order to gain approval and meet the needs of others may be gifted but may be unaware of it.

A list of Characteristics of Giftedness that are common among people who are intellectually and creatively gifted is included in the Publications section of this website.

About half of our nation’s gifted students are never identified, and even those who are identified often perform significantly below their levels of ability. Group intelligence tests, commonly used in schools for screening purposes, often fail to provide accurate assessments at upper levels of intelligence; and the performance potentials of people who think creatively frequently tend to be higher than their IQ scores suggest.

Early identification and assessment of gifted children provides parents and teachers with the information they need to structure home and school environments that are optimally beneficial to each child.

Ideally, the assessment process should begin with a comprehensive psychological evaluation designed to identify gifted children’s intellectual strengths and weaknesses and assess their emotional/social functioning, adaptive skills, and vulnerabilities as well as their creative potentials and interests. Information should also be gathered concerning their achievement motivation and locus of control as well as their grades in school in order to determine whether a child is underachieving or achieving in accord with his or her intellectual and creative potentials.

For more detailed information concerning recommended testing instruments and procedures, please refer to the article on Testing Gifted Children in the Publications section of this website.

Comprehensive evaluations should include objective, subjective, and projective procedures, which include the following:

- individual measures of intelligence;

- comprehensive academic achievement testing;

- projective psychological assessment;

- gross neurological screening;

- parent and teacher questionnaires;

- behavioral observations and clinical interviews;

- assessment of creative portfolios, as needed;

- and vocational interest testing, as needed.

Briefer assessments, as well as more intensive clinical assessments, may also be needed to meet the needs of children with other special needs or to update parts of a comprehensive evaluation with current information concerning gifted children’s changing needs, especially their instructional needs, as they proceed through school.

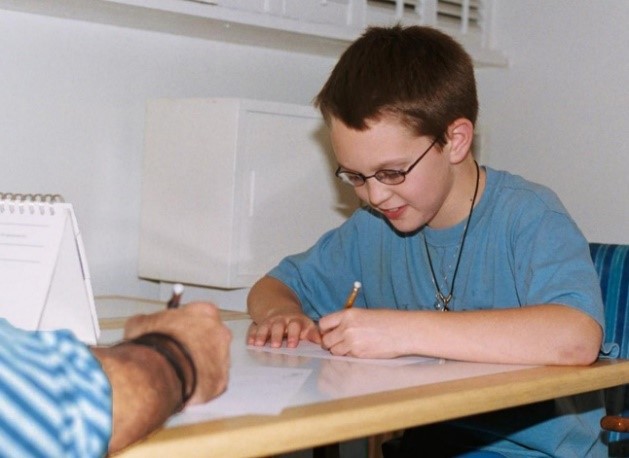

Evaluators should relate well to gifted children, who generally describe their testing experiences as enjoyable and fun. In addition, the testing conditions should be clean, quiet, and free of distractions, which can sometimes be difficult to provide in public school settings. When the testing is done in a private setting, the evaluator can take as much time as needed to establish rapport with each child, further ensuring the validity of the test results.

In the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania the tests included in each comprehensive evaluation must be administered by state-certified school psychologists. However, the results of projective psychological testing should be analyzed and interpreted by licensed clinical psychologists. When the test results are analyzed by both a clinical psychologist and a certified school psychologist, they can pool their knowledge and expertise and work collaboratively to prepare written reports with detailed explanations of the data and interpretations, as well as individualized recommendations that include specific strategies designed to foster each child’s optimal growth and development both at home and at school.

Comprehensive evaluation reports should also include information designed to educate parents and school personnel about the special needs and experiences of gifted children and adolescents, as well as about their educational rights.

The testing results should be shared during a feedback session that enables parents to ask questions about their child’s report and talk about ways to implement the recommendations, which often make significant positive differences in children’s lives.

It is important to be aware that people may be gifted or talented in different ways, which may not always be evident without adequate assessment. This is especially true for children with physical emotional, and learning disabilities. These children may be excluded from gifted programs when testing procedures fail to take into account their disabilities and when the test results are interpreted by focusing on their disabilities rather than their gifts.

If your child has an emotional, physical or learning disability, make sure the professional who evaluates him or her has experience in modifying the testing procedures and interpreting the results in accord with your child’s special needs.

More often than not, where there are differences between the results of current testing and previous evaluations, these differences have to do with factors that interfere with a child’s ability to demonstrate the extent of his or her potential with consistency.

Therefore, it is important to search for reasons for such differences and use the resulting information to develop individualized recommendations for parents and teachers.

Psychoeducational assessments of young gifted children may also reveal some degree of developmental unevenness that is not symptomatic of disability. For example, relative developmental delays in fine motor control are not uncommon among young gifted boys, and such lags generally diminish and disappear with maturity.