Differences Between Public School & Private Evaluations

Comprehensive psychological evaluations of school-age children and youth are most often conducted to assess abilities and potentials as well as to explore learning capacities and identify factors that may inhibit or enhance young people’s educational performance. Individualized educational interventions can then be recommended based on the testing results.

In a public-school setting, the information gathered during a psychological evaluation may be used in the development of a GIEP (gifted individualized education program) and GWR (gifted written report). It may also result in the identification of an educational disability and the development of an individualized education program (IEP). Public-school special education evaluations generally follow formats dictated by state educational agencies and are designed to address issues that are limited to a specific referral reason, learning or behavioral problem.

Achievement measures used in public-school settings are generally group tests such as the Terra Nova, Stanford Achievement Test, and California Achievement Test. The results of these tests are reported in terms of a student’s performance percentiles in comparison with age-mates, while achievement measures used in private settings are usually administered individually and provide information about a student’s need for individualized instruction as well as his or her academic strengths and weaknesses. This enables comparisons to be made between a student’s ability levels and achievement and can reveal discrepancies that are important not only for identifying underachievement but also for identifying creative giftedness.

Comprehensive psychological evaluations conducted in private settings may be broader, more in-depth assessments that often involve the use of additional testing instruments to determine not only levels of intellectual ability and academic achievement for educational programming, but also to explore personality variables that may influence the actualization of students’ potentials and reveal discrepancies between their abilities and achievement.

Assessment of social-emotional functioning to explore issues that influence a child’s development, behavior, and school functioning is a critical difference between psychological evaluations conducted in private settings and public-school evaluations to determine a student’s eligibility for mentally gifted programs and needs for special individualized instruction. The school evaluations tend to focus on student strengths but often exclude exploration of personality variables that may influence the actualization of students’ potentials and reveal discrepancies between their abilities and achievement.

Social-emotional evaluations included in private assessments provide information about gifted students’ emotional and social strengths, vulnerabilities and needs. They provide evidence of creative thinking; and they make it possible to identify different patterns of underachievement that need to be addressed and overcome.

What Should Private Testing Reports Include?

A private comprehensive psychological evaluation should include: background information; teacher input; testing observations; assessments of intelligence or cognitive functioning, academic achievement, and social-emotional functioning; and a concluding summary of the information gathered and specific individualized recommendations designed to assist parents and teachers in helping the student overcome any existing obstacles to learning and development and actualize his or her potentials. Evaluation of mentally gifted students should also include some appraisal of creativity since creativity is known to enhance academic performance and since creative thinking often requires teaching strategies that are different from those that are commonly used in traditional classrooms.

Background information can be gathered through a developmental history questionnaire that is completed jointly by the child’s parents. This questionnaire should be designed to gather information about the student’s family constellation, birth and early development, medical events, school history, social relationships, and recreational interests.

Information about the student’s characteristics that parents may regard as strengths and weaknesses, in addition to parents’ particular areas of concern, if any, can also be elicited.

A subsequent interview with the parents allows this information to be further explored and integrated and contributes substantially to the comprehensive evaluation process.

Input from the child’s teachers should also be solicited in order to obtain information regarding the student’s classroom functioning, attention span, interpersonal functioning, strengths and weaknesses, and creativity. Information about how teachers may currently be fostering a student’s strengths and addressing any concerns can also be queried. Input from other adults who interact with the child, such as private art and music teachers, can provide a broader perspective that adds to the learning and social-emotional profile being developed. Including information from the student’s teachers increases the likelihood that recommendations generated during the evaluation process will be heeded and implemented in the school setting.

Observations and descriptions of the child’s behavior during the actual assessment are important in determining the validity and reliability of the assessment results. If there appear to be any reasons why the current test results may not be truly reflective of the youngster’s intellectual and academic potentials, or may differ from the results of previous evaluations, they should be explored and included in the report. The student’s attitude, attention level, and task perseverance are commented upon, and evidence of creativity, sensitivity and anxiety should be noted and taken into consideration.

Testing Intelligence & Cognitive Functioning

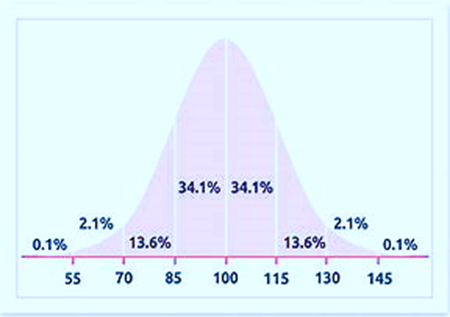

Essential in any evaluation that explores mental giftedness is an assessment of intelligence and cognitive functioning, strengths and weaknesses. Contemporary intelligence tests continue to generate a full-scale score or intelligence quotient. An IQ is a standard score, based on the normal or bell curve, where 100 is average. An overall or composite score of 130 or above (two 15-point standard deviations above the norm of 100) is traditionally indicative of mental giftedness and is the minimum score generally used by most public-school districts for inclusion in a program for mentally gifted students. However, school districts are currently being urged, and sometimes even mandated, to consider additional factors besides IQ scores that either suggest mental giftedness or may mask it.

Additional indicators of mental giftedness include creativity, intense academic prowess and/or interest, technological expertise, and leadership skills.

In Pennsylvania, three fundamental differences are used to distinguish gifted learners from other learners:

- The capacity to learn at faster rates, more in-depth and with greater complexity;

- The capacity to find, solve and act on problems more readily; and

- The capacity to manipulate abstract ideas and make connections.

Factors that can mask mental giftedness include: psychological conditions such as anxiety and depression; executive functioning deficits (which are often seen among students with developmental disorders such as Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders); and limited English proficiency.

Individually administered intelligence tests most frequently used today include the Wechsler scales and the Stanford-Binet. The current versions of both tests provide the option to generate supplementary scores, in addition to full-scale IQ’s, that exclude masking factors from the calculations and may thereby provide a truer measure of a child’s intellectual potential.

The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition, is the most recent version of the historic and highly respected test that is widely used for measuring the intellectual functioning of individuals from ages 2 through 85-plus years. The Stanford-Binet is often considered particularly appropriate for measuring the intelligence of highly functioning and advanced individuals because it includes many high-end items (to minimize a ceiling effect) and it does not place a premium on rapid responding. Since many highly intelligent individuals display very reflective and meticulous problem-solving strategies as well as a relative weakness in speeded performance on rote clerical tasks, which they sometimes perceive as boring and mundane, timed tasks may underestimate their intellectual potential. In addition, the authors of the Stanford-Binet 5 developed an experimental composite that reduces the effects of short-term memory and timed tasks and emphasizes the reasoning aspect of general ability and giftedness.

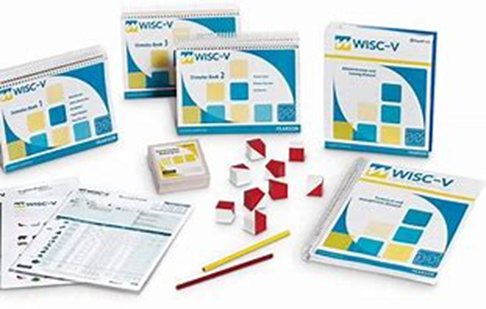

Similarly, the current version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fifth Edition (WISC-V), in addition to the primary scale scores, includes ancillary scores – such as the Nonverbal IQ and the General Ability Index – that can provide more appropriate measures of intelligence in certain circumstances. On the WISC-V, gifted children tend to earn higher scores on measures of abstract reasoning (Verbal Comprehension, Visual Spatial, and Fluid Reasoning) and lower scores on measures of processing skills (Working Memory and Processing Speed). Since weaknesses in processing skills are less relevant to advanced academic programming, practitioners in the field of gifted education recommend the use of alternate scoring methods when assessing the intellectual ability of gifted individuals. The WISC-V GAI (General Ability Index) is one such scoring method that provides a purer measure of fluid reasoning ability in students from ages 6 through 16.

Achievement Testing

Academic achievement is another essential area of assessment in comprehensive psychological evaluations. Current popular instruments that measure reading, writing and math include the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Fourth Edition (WIAT-4) and the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement, Third Edition (KTEA-III).

A measure of academic achievement that is often preferred for assessment of mentally gifted children is the Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Achievement (WJIV). It has a high ceiling, with standard scores that extend well beyond the more conventional 160 in other achievement tests. The Woodcock-Johnson also includes measures of content area knowledge (science, social studies, and humanities) that are often highly advanced among those who are mentally gifted. Determining whether and how far a student’s academic skills and knowledge lie beyond age- and grade-level norms provides crucial information for the provision of differentiated and/or accelerated academic instruction and independent learning activities.

Comparing IQ & Achievement Test Results

It is not unusual for the academic achievement scores of creatively gifted young people to be superior to their IQ scores. While such discrepancies have sometimes been regarded as evidence of so-called “overachievement,” research suggests a far more probable and positive interpretation. Research by Getzels and Jackson found that highly creative young people with IQ’s in the 120’s were capable of academic performance levels that were similar to the performance levels of their less creative peers whose IQ’s were 20 to 30 points higher (J.W. Getzels & P.W. Jackson’s Creativity and Intelligence: Explorations with Gifted Students. New York/London: John Wiley, 1962; and “The Study of Giftedness: A Multi-dimensional Approach” in W.B. Barbe & J.S. Renzulli’s Psychology and Education of the Gifted [2nd ed.]. New York: Irvington Publishers, Inc., 1975.)

During the gifted identification process, distinctions need to be made between students who have outstanding talents in the creative and performing arts and those who may or may not possess similar talents but who also perceive and process information in a creative, conceptually complex and global-simultaneous manner (which is sometimes described as divergent or outside-the-box thinking) and who are in need of special individualized instruction as creatively gifted students.

Comparing students’ IQ scores with their academic achievement test scores can reveal discrepancies between their aptitudes and achievement that need to be analyzed. Achievement test scores that are significantly below a student’s ability level (IQ) and age/grade expectancy can be an indicator of a possible learning disability; this discrepancy is one among multiple criteria that public schools use to determine eligibility for special education programming. If a student’s achievement scores are lower than his or her ability scores, but are consistent with age and grade levels, the student is typically not eligible for special education programming.

Although similar discrepancies in mentally gifted students’ scores can be a sign of academic underachievement, and patterns of achievement tend to become firmly established by the age of 9 or 10, public schools are not required to improve the underachievement of gifted students as long as they are functioning on grade level, although teachers are encouraged to do so.

If neurodevelopmental factors are ruled out through psychoeducational or neurological evaluation, social-emotional and motivational factors can be explored through personality assessment to determine the character and causes of the pattern(s) of underachievement; and concerned parents can then provide experiences and interventions that will help their underachieving mentally gifted children to recognize, confront and change maladaptive patterns of behavior that are hindering their ability to function and achieve at levels that are consistent with their abilities. Modern parenting practices also appear to be resulting in dysfunctional family patterns that involve caring parents who over-function and children, even those who are gifted, who under-function and underachieve.

Assessments of Social-Emotional Functioning

Although various aspects of personality and behavior often have significant impact on academic achievement and performance, public school gifted evaluations are much less likely to include extended assessments of a child’s social-emotional functioning than comprehensive psychological evaluations conducted in private settings. A multifaceted appraisal of the child’s social-emotional status should be obtained through the use of objective, subjective and projective personality assessment techniques. Objective personality measures include teacher and parent ratings of the child’s behavior on a hard-copy form or on a web-based program. Frequently used instruments include: the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Third Edition; the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment; and the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning, Second Edition.

For a subjective evaluation, the child is given a clinical interview and, depending on his or her maturity level, is asked to complete a self-report version of a behavior rating scale similar to those that are mentioned above.

Important information about the child’s personal assets and adaptive skills, developmental issues and vulnerabilities, and hidden or unconscious feelings and internal conflicts should also be derived from his or her responses to the intentionally ambiguous materials and tasks involved in projective personality testing. These assessment activities include projective drawings (H-T-P & K-F-D), responses to incomplete sentences, stories related to presented pictures (TAT), and perceptions of presented inkblots (Rorschach).

Information from projective personality assessment can also provide insight concerning a child’s creative potential and ideational abilities that may not be apparent on commercial, standardized measures of creativity, which have been known to have methodological limitations and questionable validity. In addition, intrapsychic dynamics revealed by projective assessment can provide insights concerning factors contributing to a child’s pattern(s) of academic underachievement and suggest individualized interventions needed to overcome these patterns (see Overcoming Underachievement in the Publications section of the Center for the Gifted website).

Projective Psychological Testing

In spite of the importance and advantages of social-emotional and personality assessment when conducting a comprehensive psychological evaluation of mentally gifted children, the level of examiner expertise and the amount of time required for projective assessment in private settings usually far surpasses what is legally mandated and can be readily accomplished in a public-school evaluation.

To obtain a complete picture of a child, a psychological assessment should include several projective instruments. These projective testing tools differ from cognitive and achievement tests in a variety of ways. Intelligence and achievement tests are designed to measure specific skills as well as knowledge in a number of academic areas. They consist of highly structured questions and tasks for which there are clear and correct or acceptable answers. The child’s performance results in numerical scores that can be compared with standardized normative data. Thus, each child’s level of intellectual ability and academic skills can be compared to that of a sampling of his or her peers.

The instruments used in a projective evaluation consist of tasks that are much more unstructured. These tasks may include requiring a child to make sense of abstract designs, compose stories about pictures, produce a variety of drawings, finish incomplete sentences, and other similar tasks. There are no right or wrong responses, and the child being tested is not only free but is encouraged to respond in whatever ways he or she sees fit.

Performance on projective testing instruments does not yield numerical scores. Although some normative data does exist for some of the instruments that are used, there is no body of data with which a person’s performance can be compared. Thus, instead of assessing children’s specific skills and knowledge, projective instruments provide a much broader view of children’s social and emotional strengths and weaknesses as well as how they perceive the world in which they live and view their place in it.

In addition, projective instruments are helpful in assessing how people live and process information about their environments. Styles of thinking and potential for creativity can be assessed as well as the inherent ability to solve complex, abstract problems.

Evaluation of such a wide range of skills through projective testing can reveal cognitive strengths that might not be apparent in more structured, formal cognitive assessments, and this data can be very useful in understanding factors that may be contributing to a child’s apparent lack of motivation or underachievement in school.

Through projective testing, it is also possible to observe how a child makes use of his or her capacity to cope with external problems and distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive uses of such abilities. Thus, one person might be highly motivated to master difficult external situations actively, while others may use such skills to withdraw from challenges and seek through fantasy those things they feel are lacking in reality and/or to protect themselves from anticipated harm. The results of projective testing can make it possible to pinpoint areas that could be encouraged as well as behaviors that may be interfering with a child’s functioning.

Because a projective evaluation is based on instruments without specific scores or solid normative data with which a person’s performance can be compared, interpretation of the results of such tests can be rather subjective, as well as dependent on the expertise of the interpreter. It is therefore necessary to use a number of different projective instruments in order to observe consistent patterns as well as to obtain confirmation of any hypotheses regarding a person’s issues.

Once a pattern of functioning has been confirmed, it is possible to arrive at a highly individualized sense of who a person is, how s/he feels about him- or herself and significant others, how she/he thinks about and manages whatever challenges and problems may occur, and how effective s/he is at dealing with such challenges.

Integrating & Sharing the Testing Results

Once the direct assessment is complete, the information obtained should then be integrated with parent and teacher inputs to produce a comprehensive profile of the child’s abilities, personality, assets, limitations, risk factors and potentials. This often enables adults involved with the child to perceive elements of their own experiences with him or her that may have been outside of their awareness and helps to clarify aspects of the child’s ability and personality that may not have previously been apparent.

Based on the data and information gathered and synthesized, specific recommendations should be tailored and suggested to address the unique interplay of components that comprise an individual’s makeup and his or her needs. First presented are recommendations for general academic programming. These may include a statement that encourages the student’s school district to consider formal mentally gifted programming if the student displays pertinent criteria. Some children who display both mental giftedness and a learning disability or some developmental disorder are characterized as twice exceptional, and their needs should be dually and respectively addressed. It is important that any programming recommendation be presented in a diplomatic and collaborative fashion in order to elicit the cooperation of the child’s school district.

Individualized Recommendations Based on the Testing Data

Recommendations derived from a comprehensive psychological evaluation should include specific instructional strategies for the child’s classroom teacher. These strategies, whether or not the student is identified as mentally gifted, should be a compendium of practical suggestions from which the teacher may choose to implement as feasible.

Finally, the evaluation report should include suggestions for the child’s parents to implement in the home and community setting. These recommendations may include parenting techniques that are designed to foster the student’s potential and encourage his or her growth towards self-actualization. Here, the parents should also be advised, both in writing and during an interpretive or feedback session with the examiner, of any further medical evaluations or psychotherapeutic interventions that may be warranted.

When test results show that a student is functioning within the Very Superior range of general intelligence and may qualify as a candidate for his or her school district’s program for mentally gifted students, parents should share the comprehensive evaluation report with school officials. In non-public school settings, it is hoped that teachers will implement as many of the instructional recommendations included in the report as possible.

A further option to consider is a shared-time placement whereby a student receives gifted support through a Gifted Individualized Education Program (GIEP) in a local public school, while his or her primary enrollment continues to be at a non-public or cyber school. Gifted children who are actively working in the performing arts often need shared-time arrangements that can be employed in different locations.

Gifted students with Very Superior reasoning abilities and potential often become bored and may feel trapped and helpless in classrooms where lock-step curriculums are limited to grade-level academic tasks and materials that are designed to reinforce skills and concepts that they have already mastered. While accelerated instruction in subject areas that are in accord with a gifted student’s own interests and abilities is often needed and can be very beneficial, other data derived from the comprehensive evaluation should be considered in making recommendations concerning how this acceleration should be done. Gradual subject acceleration with continued monitoring of the child’s academic, social and emotional adaptation to each change is necessary.

Mentoring in a collegial manner by teachers who share the gifted student’s skills or interests can also be helpful. In addition, parents and teachers should carefully consider the amount of enrichment and extracurricular activities that are planned for gifted children at home and at school; these should be chosen and prioritized with input from the students themselves.

In the absence of adequate academic challenges, and in efforts to make their inadequately challenging educational environments more interesting and bearable, gifted children may use their high energy levels and enthusiasm to race around engaging in non-sanctioned, class-disturbing activities. Consequently, they may be viewed as hyperactive and may be medicated in the absence of understanding concerning the underlying causes for the hyperactive behavior. Comprehensive psychological evaluations can help to identify those causes and make recommendations that are effective in remedying the problem.

Creatively gifted children’s responses to projective testing suggest that they tend to perceive and process information differently from peers who are less creative. They are likely to respond optimally when information is presented to them in a global-simultaneous manner that differs from what teachers usually do (in a linear-sequential manner).

Creatively gifted students need to be given the big picture first, before they are given the facts, or to be presented with problems (problem-centered learning) that engage their interests and help them focus their ideational abilities and energies in order to express them through creative products. At the same time, creatively gifted students need help recognizing the importance of developing strategies to deal with more mundane, less challenging aspects of life, and they need to learn how to verify and explain their creative ideas in linear-sequential ways that others less creative will be able to understand and support. Creatively gifted students may need to use strategies such as webbing or diagramming to explore their ideas for papers and projects and then use the webs or diagrams they have made to construct formal linear-sequential outlines that help them set priorities and focus their creative energies.

Teachers who want to encourage their students to take creative risks need to provide them with an environment where they feel safe enough to take such risks. Asking them to turn in rough drafts for review and feedback before the finished products are graded can increase creative risk taking as well as decrease the anxiety that results from competitive grading. Teachers who require their creatively gifted students to show their work, and then criticize the global-simultaneous problem-solving processes they may use to solve math problems, may unintentionally alienate these students who should instead be encouraged to prove their results in a linear-sequential manner.

Data derived from the teacher input component of a comprehensive evaluation may also reveal that a gifted student may sometimes show a tendency to share his or her advanced skills and knowledge with others in an overzealous manner. This should be regarded as evidence of an enthusiasm to contribute instead of a need to show off. At the same time, parents and teachers should encourage gifted children to take turns when making contributions in class and work collaboratively with others, as well as to show respect for other people’s ideas and use courtesy and restraint when conveying their own.

Projective psychological assessment can also reveal other problems that are common among gifted children and need to be addressed. For example, because of their advanced abilities, gifted children are often parentified in their families, which leads to a blurring of generational boundaries and makes it difficult for them to respond appropriately to adult authority and properly resolve conflicts with peers.

While gifted children may be able to converse like adults and may press to be treated as equals by authority figures, a persistent blurring of generational boundaries may leave them feeling anxious because they lack the emotional maturity and resources they need to cope effectively with all that they are able to see and understand, and they still need the security of knowing that the adults in their lives are in charge and will keep them safe.

Conclusion

A comprehensive psychological evaluation – which includes a thorough assessment of a child’s intelligence, academic skills, personality, motivation, creativity, and areas of strength and weakness, along with important information solicited from parents and educators – is a service that can support and enhance any child’s overall functioning, but particularly that of those who have special needs as intellectually and/or creatively gifted students. Implementing the individualized recommendations included in each report can foster the development and actualization of the child’s intellectual, academic, emotional, social and creative potentials.